Researchers used “groundbreaking” technology to scan a slice of jungle that was once home to a sprawling Maya city.

The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 BC in what is known as the Preclassic or Formative Period.

These people were initially solely agricultural, growing crops like corn, beans, squash and cassava, but soon became skilled traders, merchants, and even kings and queens.

They came from an area that today constitutes southeastern Mexico, the entirety of Guatemala and Belize, and some portions of Honduras and El Salvador.

Today, descendants of the Maya still live in these areas but to nowhere near the level they did hundreds of years ago when estimates suggest they numbered as many as 20 million.

Most of these people today live in Guatemala, a country which is home to the ancient site of Tikal, a place that has acted as a treasure trove for archaeologists.

Tikal, which the Maya likely called Yax Mutal, was inhabited by the ancient people as far back as 1000 BC. Archaeologists have found evidence of agricultural activity at the site dating to that time, as well as remnants of ceramics dating to 700 BC.

It sits within one of the country’s many preserved areas, deep inside dense jungle, and was explored during the Smithsonian Channel’s documentary, ‘Sacred Sites: Maya’.

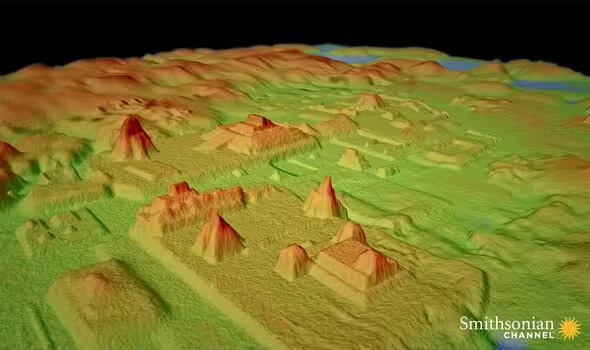

In 2017, researchers employed “groundbreaking technology” at the site to understand Tikal better, searching for any hidden gems in the undergrowth.

Using cutting-edge remote sensing technology, they were able to reveal Tikal’s true extent and find that it was in fact a city much larger than previously thought, a “collection of cities” rather than a single entity, the narrator explained.

Between 600 and 900 AD, Tikal had become a vast, bustling metropolis, a centre of trade and industry with as many as 100,000 people living there.

From relics unearthed at the site, researchers know that the people who lived there served many purposes: there were labourers and servants, architects and traders, and people all the way up to the Maya elite.

Tikal would have had its own king or queen who would have been seen as the individuals the people could contact God through.

To do this, the Maya built great sites from which they believed they could communicate with the gods.

Professor Liwy Grazioso, an archaeologist at the University of San Carlos, Guatemala, explained that with a city the size of Tikal, a few sites were simply not enough.

“All cities show you cosmogony in the way they are laid out,” he said.

“For them, pyramids were the sacred mountains to be closer to the gods in the skies.

“They were therefore very particular in deciding which temple would be facing the other.”

In its entirety, Tikal covered an area greater than 16 square kilometres and included around 3,000 structures.

What has interested researchers is the fact that Tikal isn’t a city near a river: there is no obvious way the ancient people would have got their water.

The way in which they sourced their water is ingenious: they collected rainwater and stored it through a complex system of reservoirs and storage facilities which fed the thousands of people living there.

However, rainfall in the region is wildly unpredictable and perhaps contributed to Tikal’s eventual downfall.

Tikal and much of the Maya civilisation mysteriously dwindled and disappeared around 900 AD.

Researchers have suggested a number of reasons could have accelerated the Maya’s downfall, including overpopulation, environmental degradation, tribal warfare, shifting trade routes and extended drought.

By the early 1500s, when Spanish conquistadors were making their way to the interior of Central America, Tikal had stood empty for hundreds of years.

Hernán Cortés, the Spaniard whose expedition led to the end of the Aztec Empire, passed Tikal in 1525 but made no mention of it in his letters, either because he believed it was not worth it or because it had fallen so far into the dense jungle.

Source : EXPRESS